Why do private properties have power lines? Who says a water main can cut through a farm?

As you drive, you can see the electric and telephone lines running alongside the road. There are also wires underground, and the road itself that cuts through land. But before these improvements were built, the land was owned by someone — and often still is.

The International Right of Way Association (IRWA) is an organization made up of professionals who want to “improve people’s quality of life through infrastructure development.” This group provides education for people all over the world who are involved in acquiring, developing and managing the land that hosts infrastructure. Roads, water mains, internet cables — all of these require land. Let’s break down how this land is acquired and used, and how the IRWA can guide the development of our infrastructure.

All of the land that is needed to build roads and public utilities, along with some extra space for future development, is usually under an easement. An easement allows one person to access another person’s property and/or use it for a specific purpose. It’s similar to “renting” your land; somebody pays to access your property, but the land still belongs to you and ownership rights don’t transfer. Easements are pretty common, and you should always check what easements are on your land before you buy or sell property.

There are different types of easements, but infrastructure like roadways and utility lines typically require a right-of-way easement or utility easement.

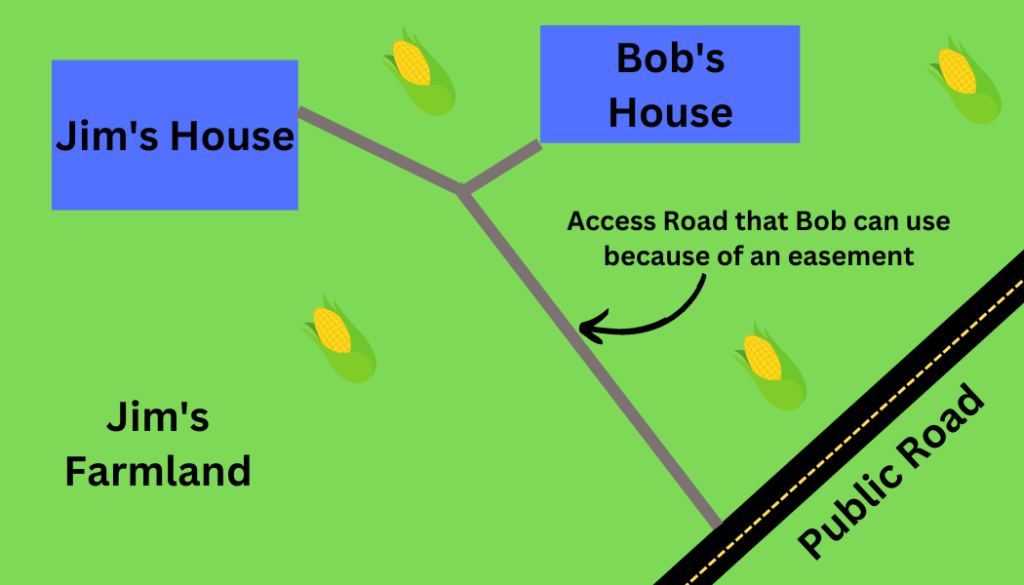

Right-of-way easements allow travel across private property. For example, if a private lot blocks access to a public area, a right-of-way easement allows people to cross a portion of the private lot to reach the public area. This portion of the lot is open to the entity specified in the easement and can be used for a specific purpose. This is a common situation in rural areas, where people own big swaths of farmland. An access road, for example, might be under a right-of-way easement.

Right-of-way easements can extend to just a few people, as in the above example. But more commonly, governments obtain public rights-of-way to build public roads and bridges. In this case, the government purchases the easement from a private landowner before building the road. After the road is built, the easement allows the public to access the landowner’s private property for the specific purpose of traveling on the road. But the public is only allowed to access the portion of the property that is in the easement, and only for traveling on the road. The easement doesn’t allow open access to private property, and the landowner can do whatever they want with the rest of their property where there isn’t an easement.

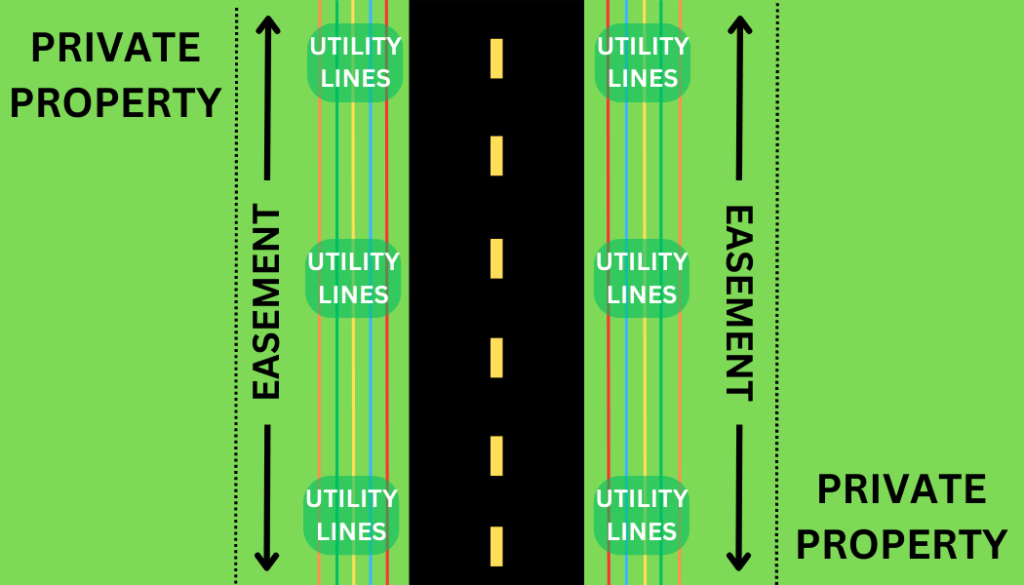

Where there’s a road and right-of-way easement, there’s usually also a utility easement. These easements are extremely common. As Jason Somers, president of Crest Real Estate, explains, utility easements allow utility companies to access private property “for the benefit of the community.” Once a utility easement is signed, a utility company can use the land to build and maintain structures like power, water, internet and telephone lines, which can be both above and below ground.

Wherever you see utility lines, there’s probably a utility easement in place. If you’ve ever come home to find spray paint on your front yard, you can assume that’s a utility company marking their underground lines on a utility easement. (Read more about what these markings mean here.) These easements are way more common than you’d realize!

Like all easements, utility easements specify who can access a piece of property, where they’re allowed to be on the property, and what they can do on the property. In this case, the easement applies to the utility company and allows them to access their utility lines. These lines require a lot of maintenance, which can be frustrating for landowners. But all of this work directly benefits the landowners and surrounding community, because utility easements are how we get electricity, water and communications.

Rights-of-way are usually easements appurtenant, which means they’re tied to the property and stand even if the owner of the land changes; they become a part of the property title. Utility easements are usually easements in gross, so they’re associated with an individual or organization rather than the property itself. When a new easement is created, the landowner is typically compensated.

The easement process can be confusing, which is partly why the IRWA was formed. They provide credentialing at different levels for people who want more industry knowledge about how to manage easements and other legal and engineering aspects of land acquisition and infrastructure construction. The IRWA mostly works with the Electric & Utilities, Transportation, Oil & Gas, and Public Agencies sectors. If you want to access resources for industry professionals or learn more about how to get involved in the right-of-way profession, check out their website.

Roads certainly aren’t going away, and we will always need infrastructure like electric, water, internet and telephone lines. As our society continues to develop, we will continue building and renovating the ways we communicate, travel and live. The IRWA aims to make this process easier for professionals across the industry.

But whether you’re a right-of-way professional or a landowner, it pays to know about easements, especially common right-of-way and utility easements. These contracts might allow people to access your land, but it doesn’t change your ownership. Agreeing to an easement is one of the best things you can do for your community, because it promotes growth and increases access to vital utilities.

We’re well-versed in easements at Heneghan and Associates, P.C., especially our transportation engineering and water/wastewater engineering teams who often deal with right-of-way and utility easements. Feel free to contact us for more information about these projects!